By Seregin A. P. (Ed.) (Серегин А. П. in Russian) - Moscow Digital Herbarium: Electronic resource. – Moscow State University, Moscow. (on line), CC BY 4.0, Wikimedia Commons.

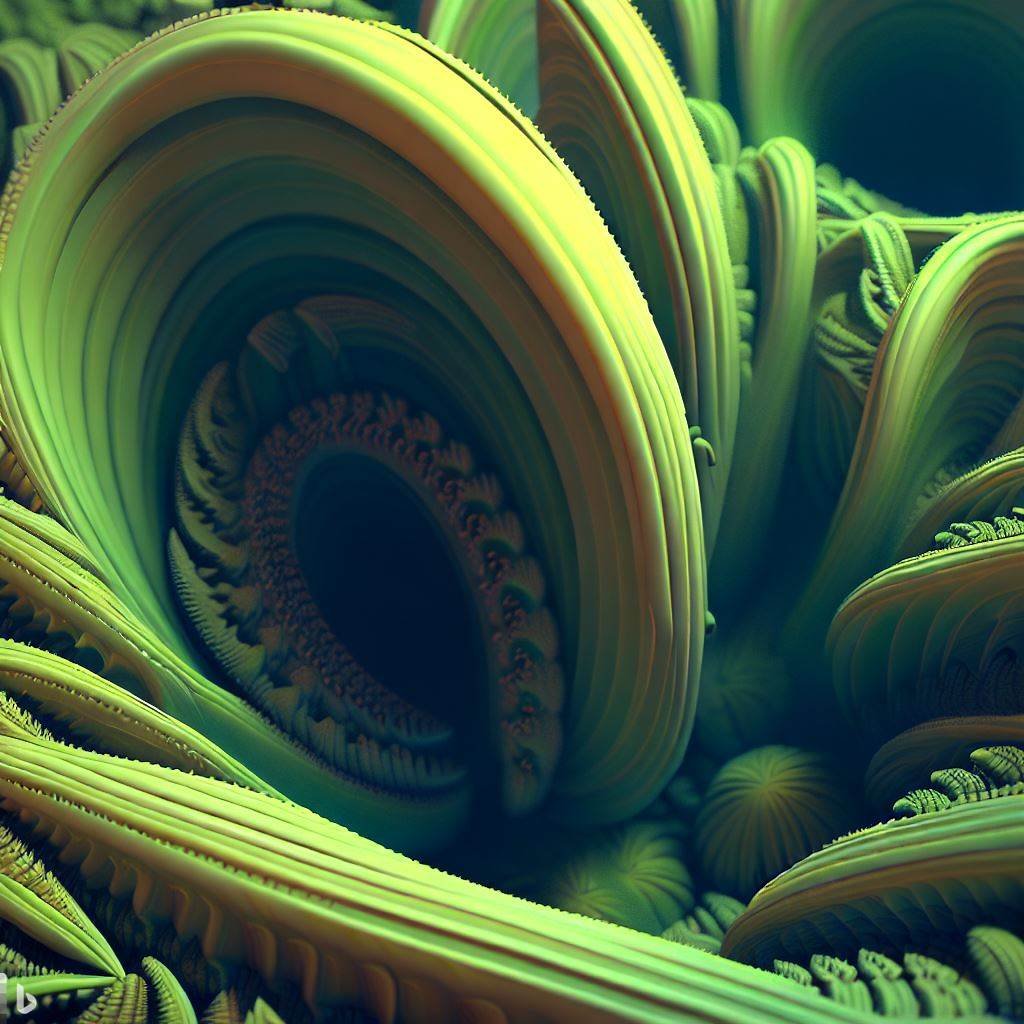

Un/Earthings and Moon Landings

An Ongoing Artistic Study

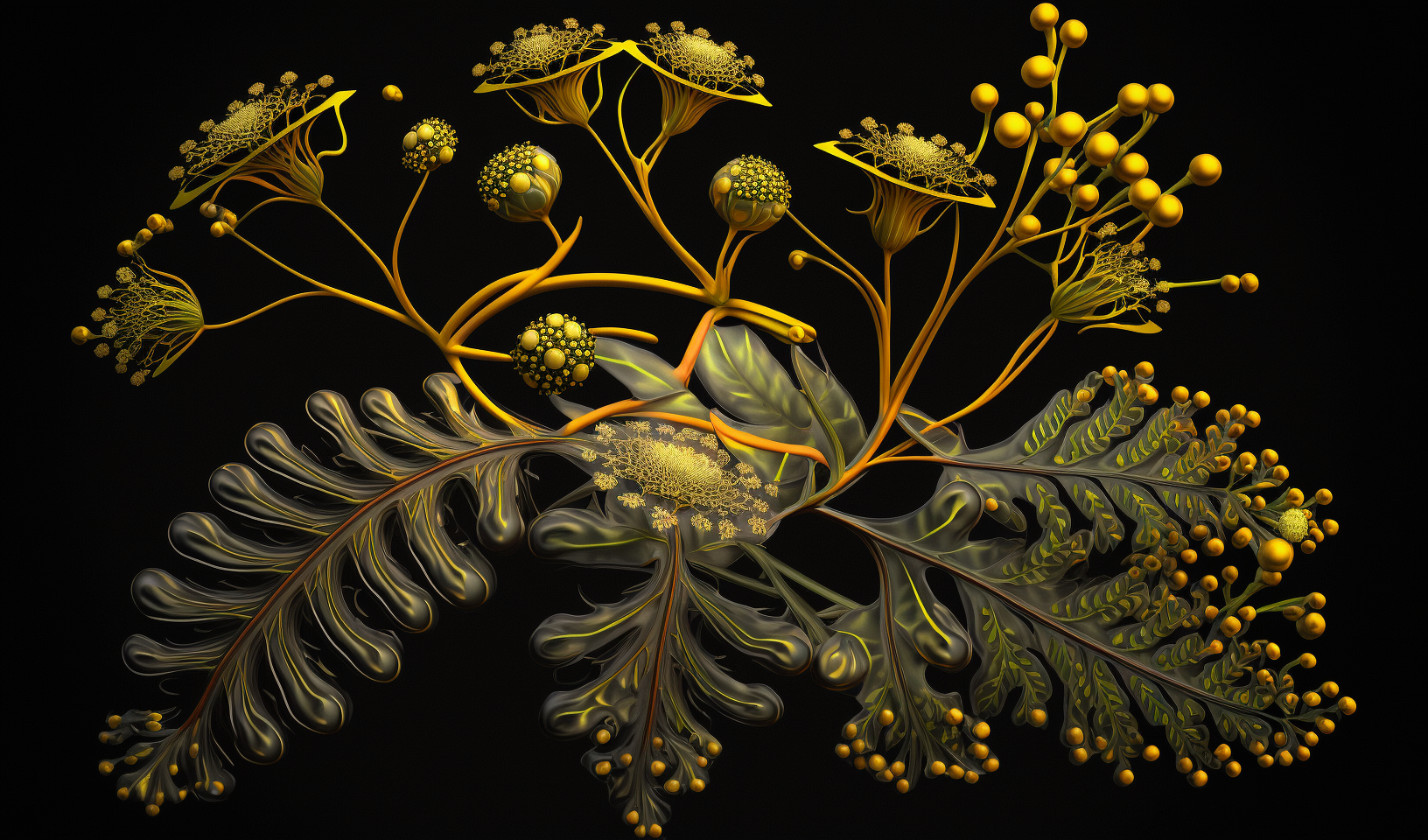

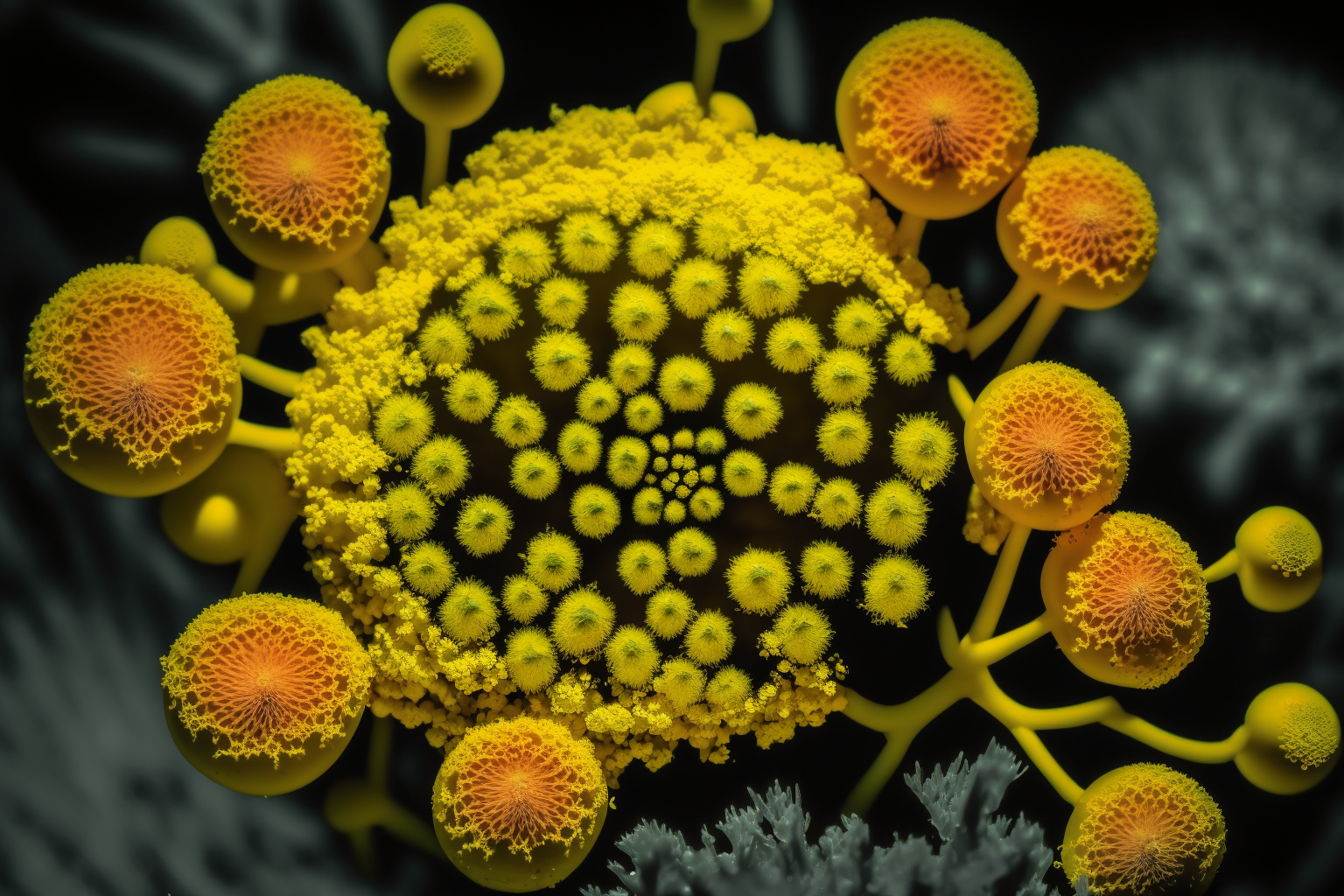

In 2021, researchers from Istanbul University reported that a plant species believed to have been extinct for almost 2,000 years might have been found in Turkey, growing around the slopes of Mt. Hasan in central Anatolia. The species, Ferula drudeana, closely resembles a fabled plant once known as silphium. This plant, likely a type of giant fennel, once grew in the dry Mediterranean landscapes surrounding the ancient city of Cyrene, located in what is today the city of Shahat, in the Eastern coast of Lybia. In Ancient Greece and Rome, silphium was valued for its medicinal and aromatic properties; historical accounts extensively document the use of its sap as a spice in Greek-Roman cuisine, as well as the use of its juice in aphrodisiac, contraceptive, abortifacient, and other medicinal preparations. In his Enquiry Into Plants, Theophrastus describes it:

“The silphium has a great deal of thick root; its stalk is like ferula in size, and is nearly as thick; the leaf, which they call maspeton, is like celery; it has a broad fruit, which is leaf-like, as it were, and is called the phyllon. The stalk lasts only a year, like that of ferula.”

In De Re Coquinaria, Roman gourmet Marcus Gavius Apicius describes the use of silphium in multiple Greek-Roman dishes as a spice for meats in classic dishes such as Parthian chicken, as well as in preparations and sauces for truffles and gourds. In his plays, Aristophanes depicts silphium as a prized delicacy consumed by the most fashionable elites of Athens. Dioscorides writes about its use as an emmenagogue, stating in De Materia Medica that “a decoction taken as a drink with pepper and myrrh induces the menstrual flow.” In a love poem to his mistress Lesbia, the Greek poet Catullus muses:

You ask how many kisses

Of yours, Lesbia, would be enough and more for me.

As great as the number of Libyan sands

That lie at Cyrene producing silphium […]

A Dance of Greed and Survival

The ancient history of silphium offers an emblematic — if daunting — example of the endlessly reenacted tragedies that define the environmental struggles of our own times. This, many historians argue, is the first documented extinction of a species due to anthropogenic activity; a dark omen of the dance of human greed.

In his text Natural History, Pliny the Elder chronicles that the plant — also known to the Romans as laser or laserpitium — first sprouted around the gardens of the Hesperides after the land was soaked by a shower of black rain, seven years before the foundation of Cyrene (700 BCE). The popularity of silphium allowed it to accrue considerable commercial value. Its image was minted in tetradrachm coins in Cyrene, meant to pay an average of four days of salary for a labourer; at one point, the Roman Empire kept 1500 pounds silphium in its treasury along with its reserves of gold and silver. Although its harvesting was highly regulated, the species was also sought after by livestock; sheep, when left unattended, would graze on it over all other plants.

Rome Is No Longer In Rome, It Is Wherever I Am (2023). Installation view by Lea Dörl.

The reasons for silphium’s disappearance have long been a matter of debate. Pliny denounced overharvesting and overgrazing as a reason for its dramatic decline, but contemporary scholars (Briggs and Jakobsson 2022; Parejko 2003; Appelbaum 1979) point out that other factors might have also been at play. Its disappearance coincides with the Roman Warm Period (250 BCE-400 CE), when higher temperatures in Europe and the North Atlantic might have affected the already arid region of Cyrene. Issues such as aridity and soil depletion might have also been further aggravated by the mismanagement of the land by Roman landowners, who — unlike local farmers — were interested in short-term profit over maintaining sustainable agricultural practices. In fact, the disappearance of silphium cannot be divorced from land disputes between indigenous populations and the Ancient Roman Empire; Parejko (2003), drawing from Appelbaum (1979) points out:

“The Roman landlords fenced off the meadows in which silphium grew to keep local flocks from decimating them. But the natives practiced a kind of agrarian terrorism by tearing down the fences and letting their flocks graze on the silphium to increase the value of the sheep’s mutton. It was even reported that some of the locals would steal at night into the land- lord’s silphium fields and merely uproot the plants.

A broader disruption of the plant’s habitat might, too, have been a contributing factor to its extinction. The excessive felling of thuon trees (Tetraclinis articulata), another prized commodity, led to soil erosion; in turn, with the decline of silphium populations, garlic — a crop valued by the Romans — was planted in its place. Slowly, cooks began to substitute silphium with other plants — most notably Ferula assa-foetida, a spice endemic to Southern Iran.

Endings as Beginnings as Endings

Silphium’s story unearths significant questions on herbal medicine, the devastation of landscapes through the forces of state and capital, migratory movements, and struggles for land and home. “Moon Landings and Un/Earthings” is an ongoing exploration of the futures/pasts/presets of this plant, working in the 4,000 year gap between its last documented sighting in the coast of Lybia, its re-emergence in central Turkey, and future Earths 2,000 years from now. What can this ghost plant, in its appearances and disappearances, tell us about our relation to eroding landscapes and the shared stories of survival in the face of the climate crisis?

This project has been granted generous support by the Fonds Darstellende Künste and Kampnagel, transmediale, and Primary Nottingham.

In case you are interested in hosting a performance, exhibition or lecture, please don’t hesitate to get in touch.